Since 1918, the United States has periodically established, rescinded, re-established and extended daylight saving time. Currently, we set our clocks ahead an hour at 2 a.m. on the second Sunday in March and set them back an hour at the same time on the first Sunday in November, which falls on the 3rd of the month in 2019. To compensate for the tilting of the Earth’s axis, a morning hour is transferred to evening in the spring and returned in the fall. Although public disfavor about this disruption seems to be growing, 70 other countries joined the United States in this annual time change.

Some sections of the United States don’t observe daylight saving time, including Hawaii, most of Arizona, Puerto Rico, the Northern Marina Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa and Guam.

Daylight time is credited with providing extra light for farmers, miners and children awaiting school buses in the early-morning darkness. It may or may not save energy. However, research suggests that this annual jarring of our normal chronobiologic rhythms may also trigger some negative effects, especially on children, the elderly and those with certain medical conditions such as cancer.

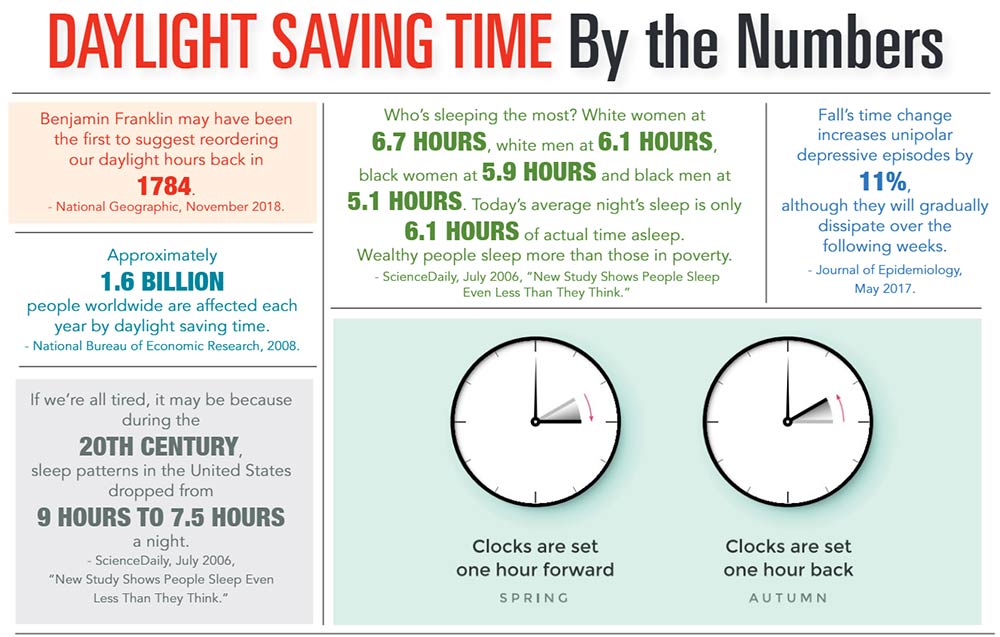

In addition to the annoyance of losing sleep, daylight saving time has also been linked to a temporary higher risk for myocardial infarctions, ischemic strokes, increased insulin resistance, depressive episodes in the fall, cluster headaches and changes in hormone levels.

Dr. William Healy, a pulmonologist with Prisma Health in the Upstate and director of the sleep lab at Prisma Health’s Hillcrest Hospital, said his patients struggle more with sleep issues in the fall than in the spring. While the loss of 40 to 50 minutes of sleep per night is felt more intensely in March, he said patients in the fall are weary, worn out and seeking assistance because their sleep patterns have been disrupted by the time change.

“With today’s growing interest in quality of life, more people are seeking help with sleep issues,” he suggested. “Less than 5% of my patients require sleep medications. The majority can make simple behavioral changes to help their bodies adjust to daylight time.”

In the spring, Dr. Healy recommended advancing bedtime in 15-minute increments a few days before the switch. In the fall, he suggested delaying bedtime in the same manner. Low-dose melatonin, an over-the-counter drug, can also help during the adjustment period.

Jennifer Mackenzie, clinical coordinator of the sleep lab at East Cooper Medical Center, advised getting some sunlight as early as possible each day to help your circadian rhythm – your internal clock – adjust to the new schedule.

“Sleep deprivation, especially in the first few days following time changes, can lead to other conditions, including irritability, morning headaches, inability to concentrate and workplace accidents,” she reported.

“People should consider going to bed earlier to get an adequate amount of sleep. I also suggest temporarily curbing nighttime caffeine, alcohol, exercise and blue-light usage. Eating your evening meal a little earlier might help, too. Fortunately, most people will only struggle for a few days to a week,” Mackenzie said.

By Janet E. Perrigo