Following on the heels of the scourge of COVID-19, parents and medical providers need to wary of a new coronavirus-linked illness called MIS-C.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children is a post-infection complication of COVID-19 found in youngsters that, while rare, is “very serious,” asserted Allison Eckard, M.D., a pediatric infectious diseases physician and division chief, pediatric infectious diseases, at the Medical University of South Carolina. While its exact cause is still unknown, it involves the immune system reacting abnormally in response to COVID-19.

Common MIS-C symptoms are an extremely high fever – MUSC has treated MIS-C patients with 105 and 106-degree fevers – rashes or red eyes and gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. It can also cause swelling of organs including the heart, lungs, brain, kidneys and liver.

“MIS-C has a lot of symptoms that are similar to other viral illnesses, which makes recognizing it very difficult,” explained Dr. Eckard. “There’s still so much we don’t know about it.”

What is known so far is that 8 is the average age of children contracting MIS-C cases, with most cases afflicting those between 1 to 14. It has occurred in kids up to age 20.

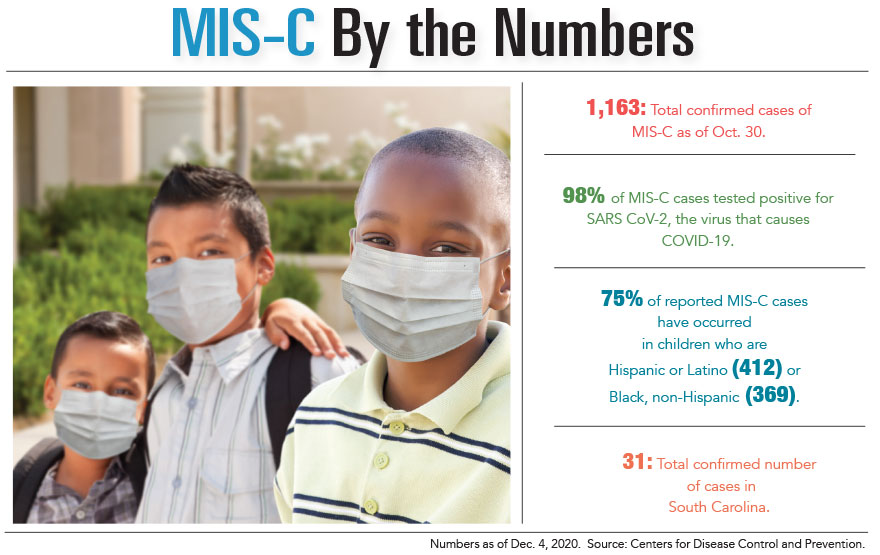

Black and Hispanic children are at higher risk of contracting MIS-C, mirroring the pattern of COVID-19 disproportionally impacting these populations.

To date, all confirmed MIS-C cases have been associated with COVID-19. Dr. Eckard added that in many cases, parents didn’t even realize their children had COVID-19 until the child tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies. This is likely because these children exhibited either mild symptoms or were asymptomatic, and kids typically contract MIS-C two to four weeks after infection with COVID-19. In contrast to COVID-19, though, children who have MIS-C often become very sick and require a visit to the emergency room.

Robin LaCroix, M.D., a pediatric infectious diseases specialist and medical director of Prisma Health Children’s Hospital in Greenville, along with Dr. Eckard, noted that MIS-C shares a lot of the same characteristics as Kawasaki disease, a post-infection complication that causes inflammation of the blood vessels. However, Kawasaki disease is more prevalent in children of Asian and Caucasian descent.

The standard MIS-C treatments take a similar approach to those of Kawasaki disease, with the aim of “quieting a dysfunctional immune system,” said Dr. Eckard. These include intravenous immunoglobulins, which are essentially antibodies to fight disease, as well as steroids and aspirin.

“What we think they do is bind to the molecules or cells that are out of control,” she remarked.

If patients are hypotensive – have low blood pressure – or are in shock, doctors support the blood pressure and use IVIG and steroids to lessen the inflammatory response, Dr. LaCroix explained.

“The body is making an excessive immune response and doesn’t turn it off, and that’s when we need to modulate it down,” she said.

Due to the abnormal immune system response MIS-C triggers, the body’s organs and blood vessels can become inflamed and dysfunctional, putting children at higher risk of blood clots. This abnormality is treated with an anticoagulant such as aspirin to lower the clotting risk.

Experimental MIS-C Treatment

Dr. Eckard is leading the clinical trial of an investigational medication to treat MIS-C called remestemcel-L, which uses mesenchymal stromal cells from the bone marrow of healthy donors.

MUSC Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital was the first hospital in the country to use this experimental product, administering it to a 4-year-old and a 10-year-old patient, both of whom responded well to treatment.

Remestemcel-L “is infused through an IV and gets circulated in the blood as if the body is making it,” stated Dr. Eckard.

It specifically addresses the abnormalities MIS-C causes, telling other cells not to produce inflammation, and has been shown to improve blood vessel function hampered by MIS-C. The hope is that remestemcel-L can lead to better outcomes than what are not the standard treatments.

As of this writing, MUSC had treated 12 children with MIS-C and Prisma Health had treated eight. A reported 31 children total had been treated for MIS-C in South Carolina. While case numbers are small, what is alarming is that almost all MIS-C patients have been healthy individuals with no underlying medical conditions. All children seen at both MUSC and Prisma Health were previously healthy, yet they still suffered what Dr. LaCroix described as an “exaggerated systemic inflammatory response,” the result of which leads to the aforementioned organ and blood vessel inflammation.

Most MIS-C cases have occurred within the two- to three-week range of children contracting COVID-19, but the condition has developed a month later in some instances, which can stymie parents in making the connection. Dr. LaCroix recommended that parents acquire a degree of familiarity with MIS-C symptoms. Medical attention should be sought immediately for children who develop a high fever or exhibit other MIS-C symptoms, especially if they have been exposed to multiple infected people.

By the time some parents have recognized the possibility of MIS-C, their children have become critically ill, so the sooner it is detected the better the outcome, Dr. Eckard cautioned. While identifying MIS-C can be difficult, she advised that the combination of a high fever and a rash should raise red flags.

The goal is to increase awareness of the possibility and severity of MIS-C. Its long-term impacts are still unknown, but some children with MIS-C have experienced severe cardiac complications.

“This is a big deal, even though it’s rare,” Dr. Eckard proclaimed.

Additional sources: South Carolina DHEC and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By Colin McCandless