In the fall of 2019, the Paris Zoological Park in France debuted a strange-looking life form: a yellowish organism with no mouth, no eyes, no stomach, no distinct shape, no evident brain, no clear means of transportation and no apparent way to defend itself.

Yet observers were told that this creature – a slime mold that looks like a tree fungus – can detect and digest food, learn and store memory, heal itself after it’s been broken into pieces, move from place to place on its own and grow at will.

If it sounds like the beginning of a bad science fiction horror movie from the 1950s, the truth might soon be even more disturbing. Because while the Paris Zoo slime mold has so far been harmless, a number of its relatives have become a world threat of fungal pathogens. Scientists now theorize that unless something can be done in time to halt their growing strength and prevalence, these pathogens will not only keep spreading, but become deadlier than anything dreamed up in a movie.

“Fungal diseases kill more than 1.5 million and affect over a billion people,” said Felix Bongomin, clinical researcher and physician at Gulu University in Uganda, Africa. “However, they are still a neglected topic by public health authorities, even though most deaths from fungal diseases are avoidable.”

While most humans have the immunity and internal guards to withstand or fight off the presence of an invading fungus, fungal pathogens operate in similar ways to the COVID strains: Their best chance for causing illness is in bodies that have been weakened by other diseases.

People suffering from cancer, lung diseases and HIV/AIDS are at high risk, as are stem-cell patients and those who have had organ transplants. However, even people with healthy bodies can be a target for invasive fungi.

For example, the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections, an international foundation focused on raising awareness of and collecting worldwide data on fungal disease, estimates that 1.4 million people go blind each year due to fungal keratitis, an infection of the cornea.

“And nearly 1 billion people have skin mycoses – which makes this disease only slightly less common on the planet than headaches and dental caries,” said David Denning, CEO of GAFFI and professor of Infectious Diseases and Global Health at The University of Manchester in England.

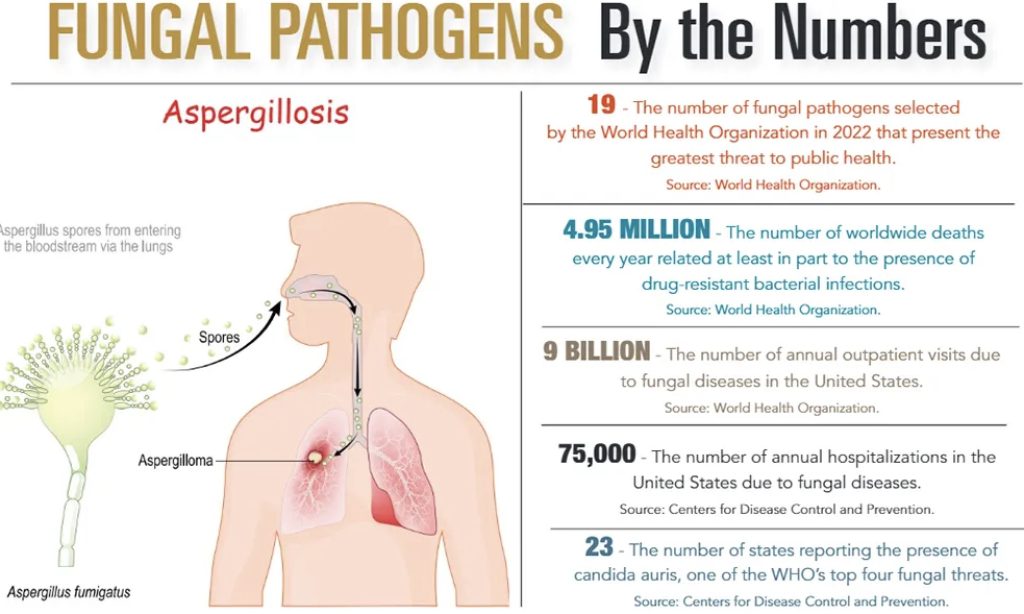

In an October 2022 report, The World Health Organization released its first-ever list of 19 health-threatening fungi. The most menacing to human health are these four:

• Cryptococcus neoformans. This is an opportunistic fungal pathogen acquired when fungi are inhaled from the environment. Infection can occur in apparently healthy individuals, and mortality rates range from 41% to 61%, especially in patients with HIV infection.

• Candida auris. This is a yeast that can produce invasive candidiasis, a life-threatening disease with high mortality and high outbreak potential. It is intrinsically resistant to most available antifungal medicines. It is also difficult to identify by conventional techniques. Although treatment guidelines are well-established, preventive measures are at best irregular, and recommended antifungals are unavailable in many countries.

• Aspergillus fumigatus. This ubiquitous environmental mold is inhaled from the environment, predominantly causing pulmonary disease, but can disseminate to other places in the body, such as the brain. Especially concerning is the emerging resistance to azoles, compounds used for treating systemic fungal infections. The mold can produce invasive infections, mainly in the respiratory system, but can circulate to other organs, particularly the central nervous system.

• Candida albicans. This fungal pathogen is a globally distributed pathogenic yeast, and a life-threatening disease with high mortality. It can be part of the healthy human microbiome, the community of microorganisms that naturally live on our bodies and inside us. But it may also cause infections of the mucus membrane or produce invasive candidiasis. While treatment is possible, antifungal resistance remains low, and critically ill and immunocompromised patients are especially affected.

“Annually, over 150 million severe cases of fungal infections occur worldwide,” said researcher Didac Carmona-Gutierrez of the University of Graz, Austria, in a 2020 report for Microbial Cell, a journal concerning unicellular biology and human disease.

A number of researchers who contributed to the 2022 WHO fungal report stated that “Drug-resistant bacterial infections are estimated to directly cause 1.27 million deaths and to contribute to approximately 4.95 million deaths every year, with the greatest burden in resource-limited settings.”

But Dr. Paula Cannon, distinguished professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, pointed out that even resource-rich nations, such as the United States and Canada, are just as vulnerable to fungal spread.

“Humans are changing – and many more people are susceptible due to immune deficiencies,” Dr. Cannon said. “And we are also seeing real-time evolution, such as with the multidrug resistant candida, which can form colonies in the liver, spleen, kidney and even the brain. It has caused bad outbreaks in hospitals, and the CDC now recognizes it as a real public health threat.”

As of October 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified that candida auris alone had spread to 23 U.S. states, including South Carolina.

The question is whether future vaccines can outpace the fungal threats before the problem gets too far.

“Life is a constant competition, a battle among all living things to evolve and get an advantage over an environment and exploit a potential new niche or food source,” she said. “We should not consider ourselves safe from that – to a fungus, we are not special, just yummy. So even with people working on obscure things like fungi, you never know what knowledge we will need to survive the next problem nature throws at us. So let’s keep supporting these efforts.”

By L. C. Leach III