Soon after Tara Hamlin got pregnant with her first son, she had to undergo surgery to have an ovarian cyst removed – which doctors warned could potentially get larger, rupture and kill both mother and baby. Fortunately, Brady, also known as “miracle baby No. 1,” was born safely in 2004, and, just four months later, Tara was unexpectedly pregnant again with a second son.

“Because of my issues with the first pregnancy, doctors performed a couple of ultrasounds but didn’t detect anything,” Tara recalled.

But when Noah Hamlin was born in September 2005, doctors informed Tara and her husband Michael that the infant had a heart murmur. Though Tara’s regular OBGYN disagreed, the couple kept an appointment to get their second baby checked out, and Noah had his first-ever cardiology appointment at Greenville Memorial Hospital just 10 days later. The results of that appointment turned out to be bad news: Noah had a ventricular septal defect — a hole in the heart causing blood to flow back into the lungs instead of throughout the body.

“It was shocking to hear,” Tara said. “We did not believe it at first. I remember on the way home from the cardiologist’s office just being stunned. I was scared to death because they said if you have any other children, the chance of this defect increases. So we made the decision right then not to have any more.”

As Noah transitioned from babyhood to toddlerhood, his parents kept a watchful eye over him. The family went to the cardiologist quarterly in the beginning, and Noah took medication to “keep his lungs dry,” Tara said. Despite these difficulties, the child had plenty of good times in his early years. In fact, by the time Noah turned 2, doctors thought the hole in his heart was closing. They even weaned him off the medicine.

“At that point, it was something we had learned to deal with. He was doing well and basically normal,” Tara explained. I can remember [the boys] playing in the yard. Noah would run and then sit down to catch his breath. He played with his brother and other kids — he just stopped to rest.”

Doctors planned to close the hole up completely with surgery when the boy turned 5. But when the time arrived for the surgery – at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston – everyone was blindsided by the truth about Noah’s defect. His heart was the size of a 19-year-old’s, Tara shared, and the entire lower part of his heart wall was missing.

“We didn’t even realize how severe his defect was until the surgery,” she said.

The operation was not without challenges. Noah was uninterested in being in the hospital. He refused to let anyone draw his blood. It took not one but two rounds of medication to get him properly under anesthesia, his mother said, and he woke up after the surgery in a terrible mood — with about nine different tubes connected to his body, plus a ventilator.

Despite Noah’s grumpiness, the child’s progress was astounding. Surgery took place on a Thursday, and, by late Friday night, his care team had moved him from the pediatric cardiology intensive care unit into a regular hospital room, and he was off the ventilator. By Saturday, Tara and Michael were able to wheel their son around the hospital in a wagon.

“His mood was better, but he was still mad,” Tara chuckled. “But he’s tough as nails, always has been.”

Over the weekend, Noah was able to play a bit and sit up in a wheelchair, with most of the tubes being removed by Monday. Tuesday morning, the Hamlin family left the hospital with Noah, and “literally that afternoon he was in the swimming pool,” Tara said, adding that they were all amazed at how much healthier he seemed immediately after the surgery.

“He made fantastic progress,” she beamed. “We left Charleston Wednesday, and at home he was trying to jump off the porch. Trying to slow him down after that surgery was near impossible. He had more energy than ever. He also started gaining weight. On his sixth birthday in 2011, he was released from the cardiologist’s care.”

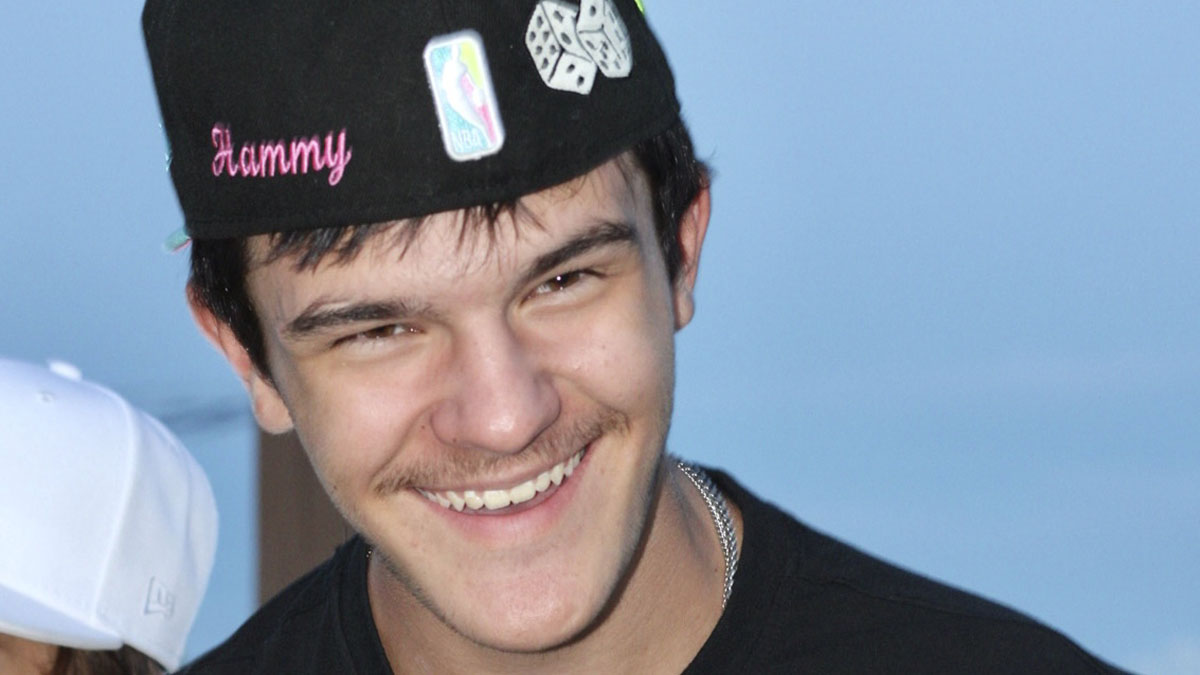

As you read this, Noah is a 17-year-old teenager who enjoys a fruitful teenage life — earning dual credits and even playing sports. He no longer has cardiology appointments and may never need one again.

“It’s all in the past now,” Tara said. “When he was released, the cardiologist said, unless there’s a complication, he can live a normal life. I don’t need to see him.”

“Now he’s on the varsity team for basketball,” she added. “I still get choked up sometimes when I see him running just fine and keeping up with his team. He just runs and runs.”

By Denise K. James