Frank Abagnale knows a thing or two about fraud.

The subject of the 2002 film “Catch Me If You Can,” Abagnale is a former teenage con artist turned respected cyber security expert and trusted advisor to the FBI for the past 43 years.

So what does Abagnale, now 71 and living in Charleston, say about scams targeting seniors that threaten their financial security and well-being?

“I’m a big believer that education is the most powerful tool to fighting crime,” he said in an interview at the Hilton Greenville, where he offered tips on fraud prevention during a free presentation as an AARP Fraud Watch Network ambassador. The event drew more than 500 people.

Many of those he encounters are younger adults concerned about their parents and hoping to help educate them. Or they’re concerned about themselves, threats to their identity and the hazards of social media.

“Millennials are actually scammed more often than seniors, but seniors lose more money because they have more money,” Abagnale said.

Seniors are prime targets because they might not hear as well or they’re dealing with a cognitive impairment but still have a passion for helping others, said Amy Carrick, who provides daily money management services for seniors in Greer.

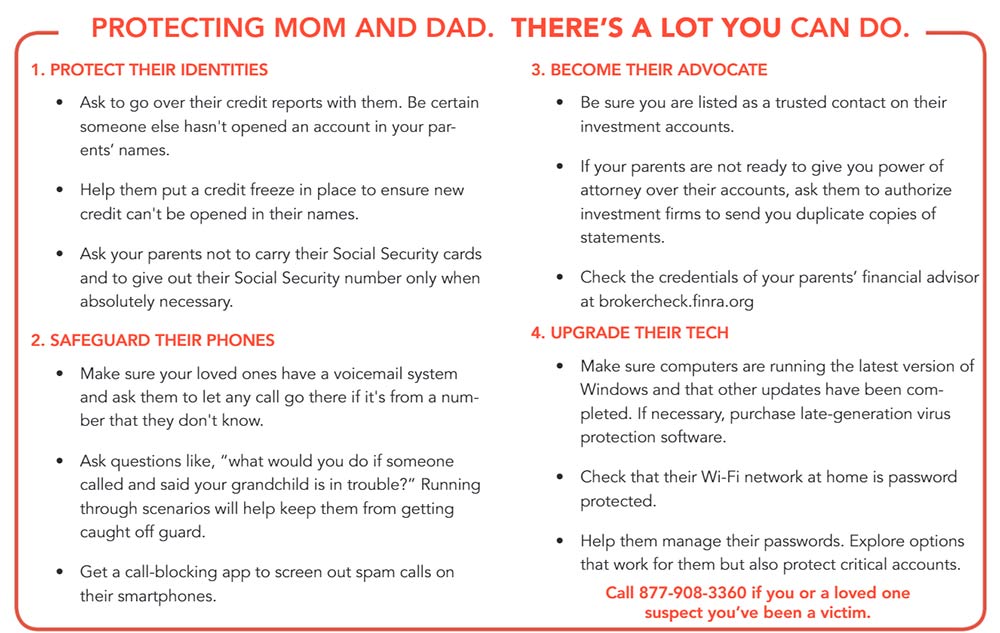

She suggested seniors consider giving power of attorney to a trusted person who is legally obligated to act in their best interests. And before they get scammed, they should assemble a team of advisors, including an attorney, a tax preparer, a financial planner, a banker and family members.

“Money makes people do strange things,” Carrick warned. “When choosing a power of attorney, sometimes family is not the best choice.”

When something goes wrong or doesn’t feel right, seniors should call someone on their team, she said. Not only are seniors lonely and generous, but they also worry about running out of money and not being technically savvy, Carrick said.

In every scam, no matter how sophisticated or amateurish, there are two red flags seniors should be aware of, Abagnale said.

The first is that at some point you’ll be asked for money, he said, and it will be immediate: “Do you have a credit card? Well, no. Can you give me your bank account number off your check, then. I’ll just withdraw it from your bank? Well, no. OK. Then I’ll stay on the phone with you. You can go down to Walmart and get a Green Dot (prepaid) card and then put the money in and then just read me the number on the back of the card.”

You also should think twice if your bank’s security department appears to call about suspicious activity on your credit card, asks if the card is in your possession and, if so, requests the three-digit security code on the back.

Abagnale said: “The second red flag is at some point I’m going to ask you for information – Social Security number, date of birth, where do you bank, what’s your credit card number?”

“Again, you didn’t solicit this call. You don’t know that it’s your bank,” Abagnale added. “They called you and said they were your bank. And everything was fine in this maybe 10-mintue conversation until the guy started to say ‘I need to verify your Social Security number. I need to verify the back of your credit card.’ That, I tell people, is the time you hang up.”

If that happens, he said, you should call the toll-free number on the back of your card and report the attempt to scam you.

Other dishonest schemes abound, including romance scams in which fraudsters prey on lonely seniors and callers attempting to trick grandparents into bailing out grandchildren who supposedly are in trouble, Abagnale and Carrick said.

Recently, the senior pastor of an Upstate church alerted his congregation, which includes many older adults, that a phishing scam was promoting his identity to solicit church members and staff. He reminded the congregation that no staff member would ever solicit parishioners directly for monetary gifts of any kind.

“Crime is constantly changing,” Abagnale said. “We have about 5,000 phishing emails in the United States every single day, seven days a week. Losses last year from phishing emails were about $12 billion.”

Most of those emails originate outside the United States, he said. It used to be you could easily identify a phishing email due to bad vocabulary or spelling and know it was a scam, Abagnale said. But scammers now go to social media, get personal or professional information about someone you know and use that real-time information in phishing emails, “which then sound so real that you don’t even question it for a second,” he said.

By David Dykes