Since COVID arrived early in 2020, there have been many increasing global health threats –pneumonia, streptococcus group A, lung infections, fungal pathogens and the mounting likelihood of additional pandemic viruses.

But one threat not that many people are talking about, which ironically comes from hospitals and facilities battling COVID, is medical waste.

For the rest of the 2020s, as COVID-related illnesses and viable treatments battle for the upper hand, medical waste is not only looming, it could easily end up deciding whether we’ll face more global concerns or enjoy the benefits of medical stability.

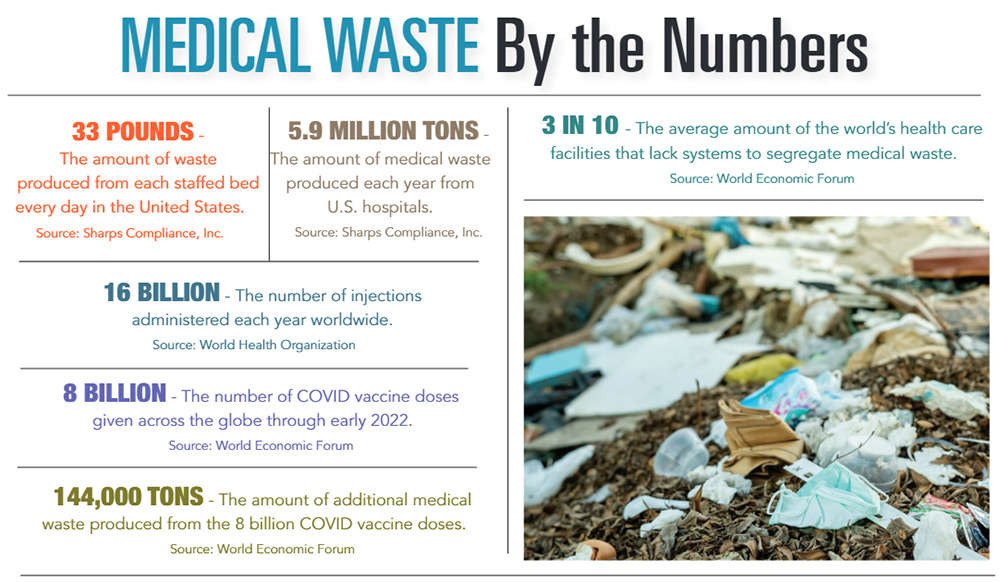

“In terms of the scale, it’s massive,” said Maggie Montgomery, technical officer with the World Health Organization. “We know that 1 in 3 care facilities globally before the pandemic lacked ways to safely segregate and treat waste.”

“[Separation] is very important because only 20% of health care waste is infectious and hazardous and requires extra care and treatment,” Montgomery said. “So we have the combined double burden of already weak systems for waste management, coupled by the fact that health workers are extremely overburdened with increased patient loads and can’t manage the existing waste, let alone extra waste.”

Examples of medical waste include blood, bandages, disposable masks, body parts removed during surgery and medical sharps – the WHO considers needles and syringes to be a substantial part of the problem because an estimated 16 billion injections are administered annually worldwide. Not all of the needles and syringes are properly disposed of afterward.

“In 2020 alone, 4.5 trillion additional disposable masks were thrown away by the public, resulting in 6 million extra tons of waste,” Montgomery said.

In the United States, federal, state, and local agencies have established regulations for that medical facilities are supposed to be following. Most of the hazardous or infectious waste is disposed of or sterilized in autoclaves – machines that use steam under pressure to kill harmful bacteria, viruses, fungi and spores. This type of waste can be put in a red bag and delivered another autoclave site.

Some hospitals, such as the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, which are registered as extra-large-quantity generators of infectious waste, have their own autoclaves.

“And all of our clinical staff participate in a mandatory waste-disposal education process,” said Heather Woolwine, MUSC director of public affairs, media relations and presidential communications. “We also post guidelines and continually reinforce the importance of proper waste disposal.”

But Montgomery pointed out that while medical personnel everywhere are trying to handle the waste issue, whether or not they are properly equipped, the extra tonnage is beginning to appear in unprecedented ways.

“There’s a lot we don’t know about plastics and the environment,” she said. “And increasingly, we’re finding that microplastics are showing up in our waterways and our food systems. These are all concerns about health care waste.”

To this end, a firm called EcoSteris, located in Summerville, has taken the initiative to handle the state’s medical waste problem with the recent construction of a $6 million state-of-the art disposal facility. It will contain an autoclave, an automation system and shredders for treating up to 19 million pounds of medical waste per year.

“With such capacity, we will be able to treat the medical waste of all the state’s major hospitals, as well as all of the doctors’ offices and clinics combined,” said Youmna Squalli, president and owner of EcoSteris. “This new facility is in a centralized spot to handle medical waste generated on both a large and small scale.”

The treatment procedure is simple: The medical waste that comes to EcoSteris gets treated first, then it is shredded twice.

When asked the difference between existing methods and EcoSteris’ new process, Squalli said that the sterilization approach, which is followed by the majority of medical waste treatment processes, allows only for treatment “but does not change its composition.”

“So you end up seeing needles and sharps in the compactors and in the landfill even after treatment,” she said. “Our facility, which is the first of its kind, will eliminate this concern.”

She added that the EcoSteris method provides an “80% to 85% reduction in volume of treated medical waste after shredding.”

“Our long-term goal is to reuse the treated and shredded waste to hopefully have zero waste sent to our landfill,” she said. “My husband, David and I have a combined 20-plus years experience in this industry, and we want this new facility to eventually be the standard adopted by medical facilities across the country to help keep medical waste from becoming another burden for us all to handle.”

By L. C. Leach III