Many parents know the agony – and challenge – of a son or daughter waking up in the middle of the night and complaining that an ear hurts. That was a regular occurrence for my wife and I as our middle daughter, crying and unable to sleep, wrestled with repeated ear infections. Numerous doctor visits and countless doses of amoxicillin finally did the trick and cleared up the problem just before we had to resort to ear tubes.

The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders said ear infections are the most common reason parents bring a child to a doctor. More than 2 million American children experience fluid in the middle ear each year, often following a cold or an acute ear infection, according to Harvard Medical School.

The condition is also called a silent ear infection because many children have no symptoms, Harvard officials said. Some children, though, may rub their ear or experience mild pain, sleep disturbances, unexplained clumsiness, muffled hearing or delays in language and speech development.

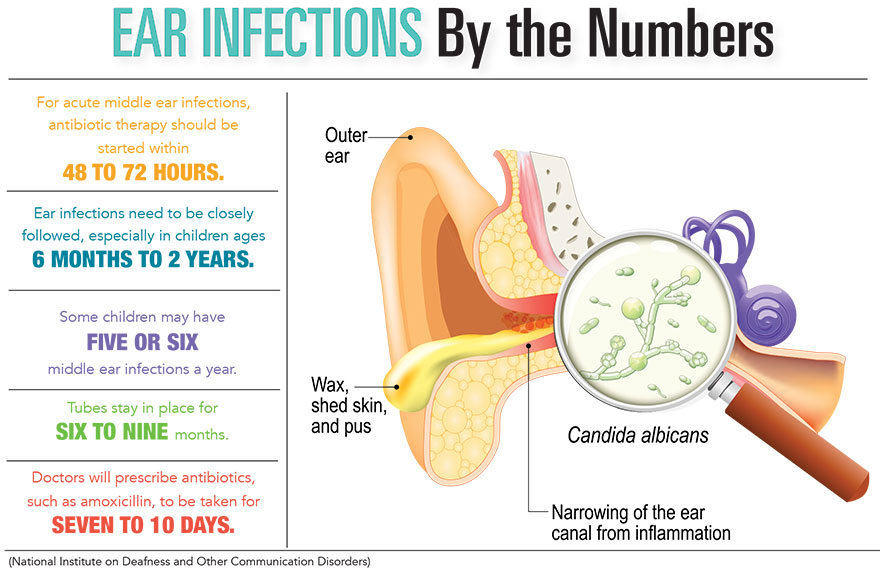

Your ear has three parts – the outer, middle and inner ear – and an infection can affect any of the three.

“To the layperson, an ear infection is any infection that’s in your ear,” said Dr. Thomas Sellner, who is with Carolina ENT in Greenville. “The distinction between the three is actually a pretty big deal.”

Acute otitis externa is the scientific name for an infection of the ear canal, part of the outer ear. AOE also is called swimmer’s ear.

Dr. Sellner and Dr. Joseph Russell, a doctor with National Allergy & ENT in the Charleston area, said doctors typically see an increase in those ear infections in the summer due to water exposure and humidity.

“The ones that you see spike in the summer are the external ear infections where you get the ear canal filled with a bacterial infection, and it’s very painful and if you touch the outside of the ear canal, it can be exquisitely tender,” Dr. Russell said.

AOE usually is treated with antibiotic eardrops, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Middle-ear infections are called otitis media, and there are two types, according to the CDC:

- Otitis media with effusion occurs when fluid builds up in the middle ear without pain, pus, fever, or other signs or symptoms of infection.

- Acute otitis media occurs when fluid builds up in the middle ear and is often caused by bacteria but can also be caused by viruses. AOM can be present in one or both ears.

The federal agency says OME usually goes away on its own, without antibiotics. An AOM sufferer might not need antibiotics because the body’s immune system can fight off the infection without help from them, according to the CDC. Sometimes, however, antibiotics are needed.

Meanwhile, inner-ear infections are “very rare to see in adults or children” and usually result from complications associated with a severe, untreated infection, Dr. Russell said.

He said doctors see a big spike in otitis media cases in children ages 6 months to about 2-and-a-half years.

Doctors and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association note that ear infections are more common in children because of the way their ears develop. We all have an eustachian tube that runs from our middle ear to the back of our throat and helps the middle ear drain. In children, the tube is smaller and is not tilted like it is with adults. That makes it easier for an infection to block the tube.

“It’s a very hospitable environment to allow bacteria or viruses to set up infection, and then that leads to those severe infections – a child screaming in the middle of the night, tugging on the ear and just seeming inconsolable at times,” Dr. Russell said.

There is a home remedy for external ear infections, but not the middle ear, he said. For those predisposed to swimmer’s ear, a few drops of a one-to-one mixture of rubbing alcohol and white vinegar in the ear canal after water exposure is “certainly fine to use,” Dr. Russell said.

Dr. Sellner added that some people use warmed sweet oil, a mixed blend of olive oil, as an old-school remedy for conditions affecting their ears. His mother used the tactic to treat his earaches when he was young.

“It does help with the discomfort. It takes some of the pressure off the eardrum,” he said. “Of course, that doesn’t help the infection. That doesn’t help the fluid. It gives you more symptomatic relief. It makes you feel better.”

Ear Tubes

The frustration of repeated ear infections can lead parents and doctors to one inescapable conclusion: It’s time for ear tubes.

If several doctor visits and multiple doses of antibiotics haven’t worked, doctors say parents should consider ear-tube placement, a relatively safe procedure with a low risk of serious complications, according to the Mayo Clinic.

“If a child has more than three such (ear) infections in six months or more than four in a year, that’s when you want to consider placing ear tubes,” said Dr. Joseph Russell, a doctor with National Allergy & ENT in the Charleston area.

Mayo Clinic officials said ear tubes are used most often to provide long-term drainage and ventilation to middle ears that have had persistent fluid buildup, chronic middle ear infections or frequent infections.

Dr. Thomas Sellner, who is with Carolina ENT in Greenville, said another guideline recommends ear tubes in cases where fluid, and not necessarily an infection, is present for more than 12 weeks straight without disappearing.

As the Mayo Clinic noted, ear tubes are tiny, hollow cylinders, usually made of plastic or metal, that are surgically inserted into the eardrum. Its website said an ear tube creates an airway that ventilates the middle ear and prevents the accumulation of fluids behind the eardrum. Ear tubes can also be called tympanostomy tubes, ventilation tubes, myringotomy tubes or pressure equalization tubes.

Surgery for ear tube placement usually requires general anesthesia.

According to the Mayo Clinic, the procedure usually takes about 15 minutes. The surgeon:

- Makes a tiny incision in the eardrum (myringotomy) with a small scalpel or laser;

- Suctions out fluids from the middle ear;

- Inserts the tube in the hole in the eardrum.

Mayo Clinic officials said that after surgery, your child is moved to a recovery room where the health care team watches for complications from the surgery and anesthesia. If there aren’t any, your child will be able to go home within a few hours.

Usually, ear tubes stay in the eardrum for six to nine months or longer and then fall out on their own. Mayo Clinic officials add that sometimes a tube doesn’t fall out and needs to be surgically removed. In some cases, the ear tube falls out too soon, and another needs to be put in.

“Most kids only ever need one set of tubes,” Dr. Sellner said. “Less than 5 percent of kids ever need a second set.”

By David Dykes