COVID-19 has added stress to the already difficult task of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s or another dementia.

“It has been devastating for a lot of families,” said Sara Perry, executive director of Respite Care Charleston, a nonprofit organization that provides support to caregivers and those living with Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia.

People providing care for a family member with Alzheimer’s or another dementia are more isolated than ever because the pandemic has disrupted support systems, said Beth Sulkowski, vice president of communications and advocacy for the South Carolina chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Sulkowski said because people living with dementia tend to be older and have underlying health conditions, they are at greater risk to exposure to COVID-19. Even with precautions, any outside person entering the home increases the risk of spreading COVID-19, she said.

“As a result, fewer family members may stop by to help, and some families may be hesitant to bring in professional caregivers. In addition, caregivers may no longer have access to social or emotional outlets such as caregiver support groups or meals out with friends,” she said.

It’s more important than ever for caregivers to pay attention to self-care, said Renee Abrams, a licensed master social worker for Health Related Home Care in Greenwood.

“You’ve got to take care of yourself to take care of someone else,” she said.

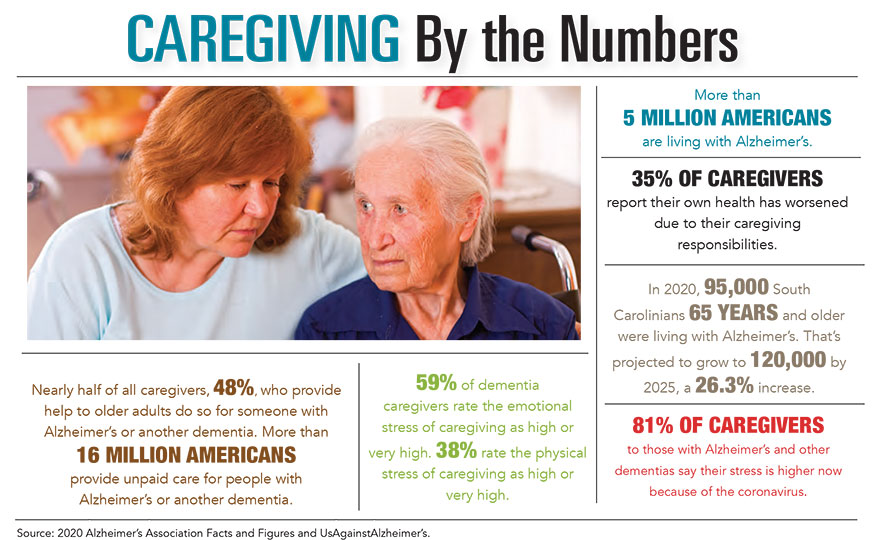

About 95,000 South Carolina residents 65 years old and older are living with Alzheimer’s, according to the 2020 Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figures report. That’s projected to climb to 120,000 people in 2025, a 26.3% increase.

More than 318,000 people in South Carolina are providing unpaid care for a family member or friend with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, South Carolina chapter. They provide 362 million hours of unpaid care, according to the report. About 30% of the caregivers are 65 or older. About 25% are “sandwich generation” caregivers, meaning they care not only for an aging parent but also for a child.

According to the 2020 Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figures Report, 35% of caregivers say their health has worsened because of their caregiving responsibilities.

“Until a person becomes a caregiver, they don’t know how hard it is,” said Abrams, who took care of her mother for three years.

And 81% of Alzheimer’s and dementia caregivers reported their stress is higher now because of the coronavirus, according to a survey by UsAgainstAlzheimer’s.

The risk of caregiver burnout, a state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion, is higher in times of increased stress, Perry said. She added that the symptoms of caregiver burnout are similar to those of depression. Burned out caregivers may turn inward and withdraw from friends and family, lose interest in activities they previously enjoyed, experience changes in appetite and feel irritable, hopeless and helpless.

There are ways caregivers can avoid burnout, Perry said, starting with asking for help. Talk to the patient’s doctor, who often can order support services such as home health, Abrams suggested. And don’t skip your own doctors’ appointments.

“Your well-being has to be the first priority. If you do not take care of yourself, you cannot care for your loved one,” Abrams said. “It’s like the pre-flight safety demonstration they do on airplanes that tells you to put your oxygen mask on first. It’s so true.”

A healthy diet, exercise and adequate sleep are vital as well.

“The most important thing is to recognize that no one can do it all alone,” Perry said. “Caregivers need to rely on those on their care team. When people say let me know if there’s ever anything I can do to help, we rarely take advantage of it.”

Many times, family and friends want to help, but they don’t know how. That’s why it helps when caregivers have specific requests, such as asking if they can sit on the porch with the loved one so the caregiver can take a nap or run errands, Perry said.

Take time for yourself, Abrams said: “Find those little moments.”

Perry also encouraged caregivers to take advantage of respite care programs, which provide temporary breaks ranging from a few hours to a brief stay in a care facility so the caregiver can go on vacation.

It’s important to recognize when the level of care a loved one needs is more than any one person can provide alone without jeopardizing their own health, Perry said. Putting a loved one in memory care is not admitting defeat, she added.

“Remember that you are not superhuman,” Sulkowski said.

The Alzheimer’s Association South Carolina chapter has a 24-hour helpline, 800-272-3900, and virtual programs through its website at www.alz.org/sc.

By Cindy Landrum