Einstein called it deceptive, Spanish artist Salvador Dali dedicated a painting to its persistence and U.S. writer William S. Burroughs once claimed that it kept people trapped within their own pasts.

They were all speaking of the human memory, how it affects people’s outlook, perspective and their ability of recall.

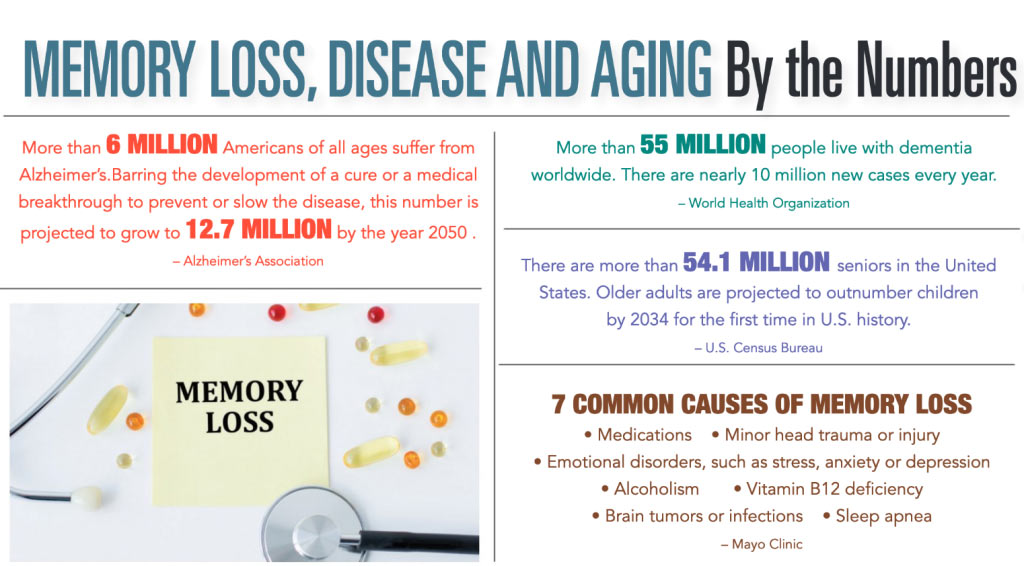

As the U.S. population keeps living longer, the human memory – and how to make it last past the age of 100 or longer – is not just a concern for seniors. It is one of the most critical elements to keeping people of any age mentally sharp and healthy.

“Memory is our ability to gather, retain and retrieve information,” said Sara Perry, certified dementia practitioner and executive director of Respite Care Charleston. “While we’re not certain how it works exactly, several different parts of the brain are engaged in the process as we recall, recognize, recollect and re-learn information.”

In that process are all kinds of memory that can be triggered or eliminated, gradually or swiftly.

Big, Small and Inexplicable

Ask any hundred people who grew up in the 1940s where they were and what they were doing when they heard about the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Chances are that every one of them could remember. But ask any hundred people now what their current car insurance policy covers, and they are likely to respond with more shrugs than answers.

Perry pointed out that while things like a personal insurance policy might seem more important for someone to remember, both short- and long-term memory are tied to its significance “and the amount of attention we give it.”

“If you forget what you walked into the kitchen for, chances are you were distracted or not that focused on why you went there,” Perry said. “On the other hand, most people can remember exactly where they were and what they were doing when they learned of JFK’s assassination or the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. Those were major events that had a tremendous impact on almost everyone alive at the time, so we paid more attention and are more likely to remember them.”

And, of course, there is the inexplicable flyby, the memory long forgotten – like a casual comment 50 years ago from a grade-school classmate – that suddenly comes back.

“Everyone forgets things, regardless of age,” Perry said. “And while occasional lapses of memory are normal as we grow older, significant memory loss and cognitive decline that impairs day-to-day life are not normal parts of aging and should be discussed with your doctor.”

Younger All the Time

Aging itself is becoming a more relative factor in both memory loss and retention.

Consider Peggy, a three-year resident of Mount Pleasant Gardens, an Alzheimer’s community that serves 64 residents. Every day, Peggy exercises, listens to music and figures out puzzles – the same things she when she was 20 or 30.

“But age has a tendency to change you,” she said.

When it does, the battle for memory begins.

“Short-term memory in our residents is the first memory to go,” said Denise Kish, executive director of Mount Pleasant Gardens. “Our residents have a mixture of long-term memory and some short-term. And we try to keep the short-term going by doing consistent events each day.”

But Kish, Perry and Charleston senior consultant Diane Sancho all pointed out that memory loss and disease are not exclusive to seniors.

“Though less common, younger adults can have dementia, too,” Perry said. “Respite Care Charleston has served many people in the community who began showing signs of memory loss in their 40s, several of whom had late-stage dementia or succumbed to the disease in their early 50s.”

Sancho, executive director of Alice’s Clubhouse Memory Care Day Center, who has worked with senior-living communities for more than 20 years, said people needing help from early-stage memory loss “are much younger now.”

“We have had nurses, artists, contractors, mayors, lawyers, corporals, an anesthesiologist and a university professor who taught six languages, to name just a few,” said Sancho. “Very few have prior brain injuries, and the majority of our newest members are in their late 60s and mid-70s – far younger now than when I started. Wish I knew the answer to why.”

Reducing Risk

Because of the innumerable, subtle differences between each individual brain, finding an answer, or perhaps many answers, is nearly as complex as the brain itself.

Dr. Mendell Rimer, professor at the Texas A&M University College of Medicine, reported in 2018 that synapses, which serve to connect the brain to the rest of our body – are not only “essential for life” but that memory may also involve the creation of new synapses.

“Synapses underlie our memory formation and learning,” Dr. Rimer said. “In dementia, synapse loss or weakening would therefore lead to decreased learning ability, memory loss and memory disorders.”

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia, both Sancho and Perry said their members and patients intend to keep every part of their memory in every way possible – regardless of their individual condition or treatment.

“Our members at Alice’s Clubhouse are in early-to mid-stage dementia, and the day center is a place they look forward to joining,” Sancho said.

And Perry added that while her Respite Care patients walk, play chess, take Spanish lessons, eat the right foods and read books to keep their memory fresh and vibrant, it’s still a gamble.

“If I had it all to do over again, I don’t know what I’d do differently, because I don’t know what caused my dementia,” said Fred, a patient at Respite Care Charleston. “You can still get it even if you do everything right.”

By L. C. Leach III