(Editor’s Note: This story is the second in a three-part series of articles on kidney transplants, kidney health and disease prevention. In her early 50s, the writer learned that she had only one functional kidney; she was also diagnosed with kidney disease that was the result of overuse of over the counter ibuprofen. She had no idea. Read part 1 and part 3 in this series.)

Cathy Self was committed to her decision to donate a kidney to her good friend Linda Burns, but that didn’t mean she never stopped and asked herself: ‘Do I really want to do this?’

Like any big decision, she said, “You either commit or you don’t.”

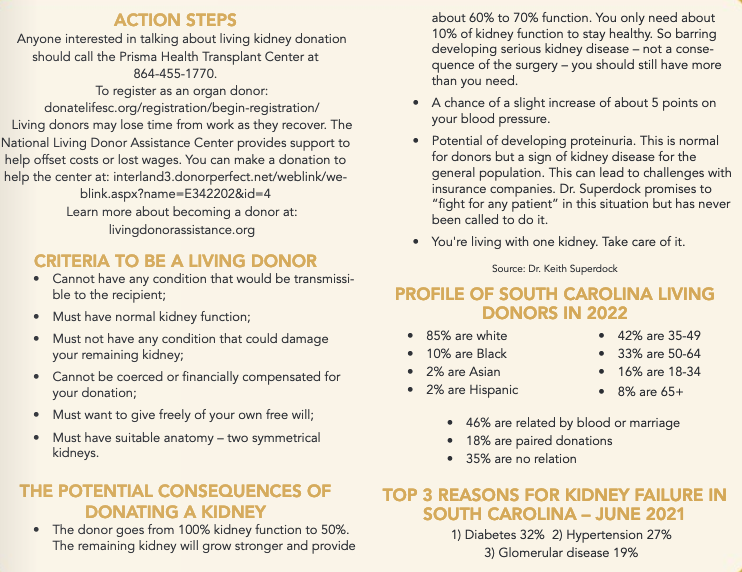

Cathy Self committed. And with that commitment, she became one of 49 living donors who have given a kidney to a friend, a spouse, a sibling or a stranger in South Carolina so far this year. Another 159 patients received a transplant from a deceased donor.

Living donors are “inspiring,” to Dr. Keith Superdock, nephrologist and co-director of the Prisma Health Transplant Center, and “a privilege to work with” to transplant coordinator Shelby Herndon.

But there are far too few of them. Currently, 1,363 South Carolinians are on the national waiting list with the average wait time for a transplant of 3.5 years. This year, according to the national organ procurement network, 10% of wait-listed South Carolina patients have died or been removed from the list because they were too ill for a transplant.

“It’s not that people aren’t willing to donate,” Herndon explained. “It’s because they aren’t healthy enough. It’s like finding a needle in a haystack.”

The donor evaluation process begins with blood and tissue screening. Surprisingly, it’s not as difficult for unrelated donors to match today, according to Dr. Superdock.

“The degree of match between recipient and donor has become less important because the drugs we use to prevent rejection have become more effective,” he explained.

Rigorous testing is, however, designed to assess the donor’s health condition, which must be “perfect,” Dr. Superdock said, adding that the confidence that the donor’s “residual kidney function will be more than enough to sustain them through a full life” is essential. Otherwise, the transplant would be unethical.

This can be a problem in South Carolina and the Southeast, where diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity are among the highest in the nation – and they also are three kidney killers.

“That means we have more people who need a kidney transplant and fewer people who can donate a kidney,” according to Dr. Superdock.

Kidney failure is a more prevalent among African-Americans.

“A lot of diseases that travel within the Black population affect the whole family. Oftentimes, if hypertension results in kidney disease in one member of the family, it affects multiple members of that family due to similar genetic makeup,” Dr. Superdock noted.

Because of this deliberative process, those who do end up donating face minimal risk, relatively quick recovery and few, if any, limitations on a normal life. But for the recipient, the difference between a living kidney and one from a deceased person one can mean years of life. Dr. Superdock said a kidney received from a deceased donor has an average survival rate of 10 years, compared with 15 years for a living donor transplant. In some circumstances, kidneys from living donors have been known to last as long as 40 years.

Herndon, the first contact for patients and donors, shepherds them through the testing process and delivers the good or bad news. But as a “fixer,” she doesn’t believe in giving up. That’s where paired donation comes in.

“We still work them up and get them approved to donate, but they don’t donate directly to the person they know,” she explained.

The paired program is a nationwide network that connects approved donors with waiting recipients across the country who also have donors who are not a match for them.

“We do an even swap. The donor here donates to the other patient, and their donor donates to the patient here,” Herndon explained.

Donors are reminded that they can withdraw any time, right up until the gurney rolls into the operating room – and donors do back out. In the cases of altruistic donors – those who don’t know the recipient – it’s less problematic. But when it’s a couple or family members and the donor decides to withdraw, transplant coordinators like Herndon offer a reasonable cover story to protect relationships.

Nine South Carolina patients received their kidney transplants so far this year through the paired donation program. Overwhelmingly, however, most transplants come from deceased donors. Dr. Todd Merchen, director of the Prisma Health Transplant Center, urges people to sign up to be an organ donor.

“Organ procurement is a difficult conversation no matter what,” he explained. “If you can bring yourself to make that decision and take the responsibility off your loved ones, it would lead to more organ transplants and families with more certainty about what to do – and less stress on what the worst day of their lives is already.”

As for Self, she went home four days after surgery and went back to her job as a Greenville County special education teacher after six weeks. Would she do it again?

“Yes. And for the same reason: I could not sit back and watch my friend die knowing I could have helped her.”

Source: All the statistics in this article come from UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing (https://unos.org/data/).

By Laura Haight