Did you know the unemployment rate for people involved in the criminal justice system is five times higher than the rate of someone who is not? By answering “yes” to questions about felony convictions on job applications, most formerly incarcerated people are taken out of the “to interview” pile. This leads to a desperate cycle of additional crime; nationally, 67% of those released from prison are re-arrested within three years.

Much of this can be attributed to the systemic issues that drove people to crime in the first place: poverty; substance abuse; lack of education; and little access to jobs that pay a living wage.

A dearth of rehabilitation and job training programs within the prison systems adds to the problem. Many people emerge from behind bars in debt from legal fees and with no prospects for gainful employment. Their transition to the world outside fails before they even get started.

But what if there were in-prison programs that taught skills so valuable that, by the time people are released, they’re a hot commodity in the labor market? And what if those skills improved the lives of children who, like many incarcerated people, were born with the cards stacked against them?

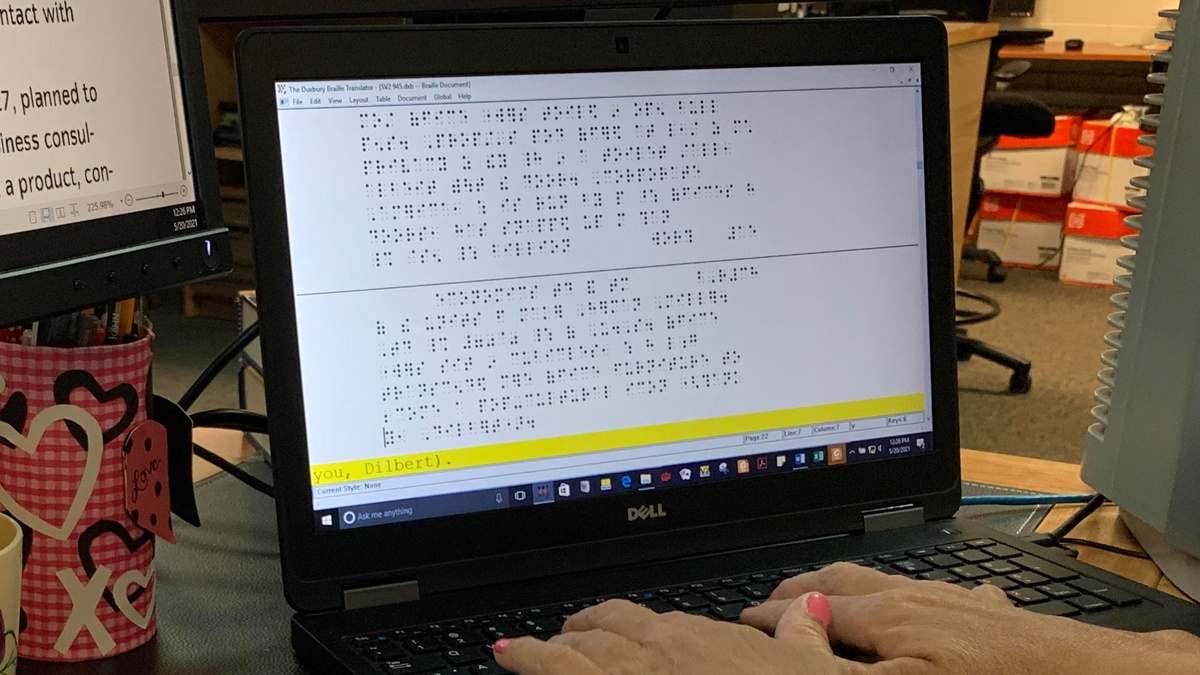

The Braille Production Center at Leath Correctional Institution in Greenwood, South Carolina, is doing exactly that. By training incarcerated women to transcribe school textbooks into Braille books for blind students, the facility is providing a crucial service. At the same time, it is instilling in its trainees both work ethic and a skill so valuable that, upon release from prison, they can find lucrative employment outside the prison walls.

The Braille Production Center was floundering in 2006 when the South Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind was approached with an idea: the school could purchase and run the facility, and the prison would provide the labor. According to Scott Falcone, director of the school’s Division of Outreach Services, the decision was a no-brainer. The school purchased the facility, received funding from the state Department of Education and was off to the races.

“It’s been so rewarding,” Falcone said.

The Braille Production Center can employ 21 women transcribing and two workers binding and shipping books across the state. Although it was shut down in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and is currently operating with a skeleton staff, the Center will ramp back up in the coming months.

Jill Ischinger, who runs the Center, choosing women from Leath to enter the program and begin training, seeks certain criteria.

“We look for a high school education,” said Ischinger. “Some college and math skills. They take an aptitude test, and we look at those results.”

They also must have at least 10 years left on their sentence, “because it takes so long to invest in them and their training.”

Literary Braille transcription is no joke. Initial training takes anywhere from nine months to a year.

“Contractions in Braille are enough to make me want to hit my head against a brick wall,” Falcone laughed.

Here’s how Braille works: Each letter is created with a series of one to six raised dots on a page that sight-impaired people can read with their fingertips. It seems simple until you add in numbers using those same dots. And punctuation. And special symbols for math and science. And … and … and. The list goes on, and what started as a simple coding system becomes overwhelming. Those “contractions” mentioned by Falcone are shortened versions of common words such as “day” or “mother” or “father” or even “character.” It’s obvious why training takes so long, but that’s just the beginning.

“We let them go as far as they want to go,” said Ischinger.

That includes special courses in textbook formatting, math code certifications, music certifications and even proofreading. Once a woman is accepted into the program, she’s encouraged to keep learning.

At full capacity, the Center produces up to 40 or so textbooks annually. That said, there generally are upwards of 60 books in production at any given time. Early elementary books are easy – a second grade social studies textbook might take six months to transcribe, format, proofread and print. High school is a different matter entirely. The record for longest transcription was a pre-calculus textbook that took more than three years!

The Center works closely with area schools. If a teacher submits a syllabus that requires certain chapters out of order, the Center will move mountains to get those chapters ready by the deadlines.

All of this hard work pays off for the women of the Center in myriad ways.

“It was a turnaround in my life,” said Cynthia Stubbs, who worked in the Braille Production Center during her years at Leath Correctional Facility. “It was my getaway. I lived and breathed Braille. Once I start something, I want to be successful. For Braille transcription, you really have to study. It can be tedious.”

She’d work in the Center during the day, then take newspapers to her dormitory to practice at night. The course stresses quality over speed, and, as a final exam, students submit a 35-page manuscript to the Library of Congress to be checked by a blind copy editor. Stubbs passed and later received certifications in textbook formatting and Nemeth math codes. The work gave her a purpose.

“I was helping a child receive an education,” she said.

Around the time of Stubbs’ release, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety was looking for someone to head a similar Braille transcription program. Administrators at Leath suggested Stubbs.

“The school backed me 100%,” she said. “I did a phone interview, and they hired me on the spot. I left Leath after 14 years on Feb. 1, 2011, and I walked back into prison 21 days later.”

Only this time, she was a free woman.

Stubbs keeps in touch with other ladies from the Braille Production Center who have left prison. Two of them work in Braille transcription at Georgia Tech; others do lucrative freelance Braille transcription work. None have been re-incarcerated since their release.

The Braille Production Center at Leath Correctional Institution is changing lives every day. By providing textbooks to sight-impaired children, the Center helps deserving children, and by giving incarcerated women skills that can be used on the outside, it’s breaking the national re-arrest chain, one woman at a time.

By Leah Rhyne