“There’s a lot of fear, a lot of mistrust of health care providers,” said Chase Glenn.

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and gender and sexuality expressions beyond the cis-gender, heterosexual norm (LGBTQ) community has struggled to find health care sensitive to their needs and experiences.

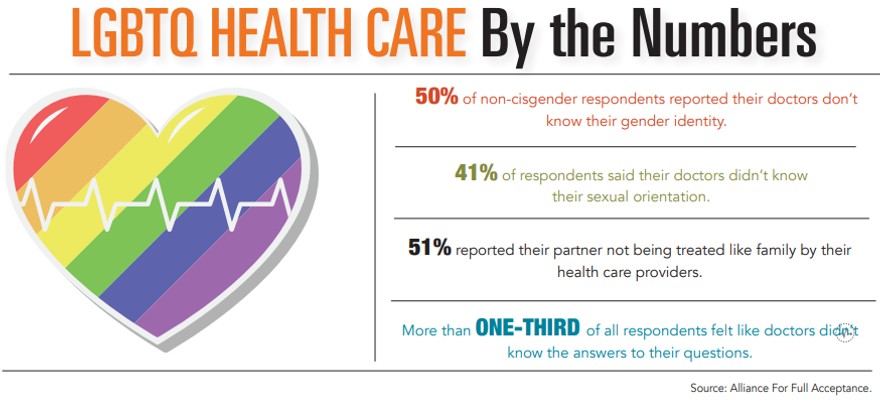

Many LGBTQ patients are hesitant to share their gender and sexuality experiences, reducing the proficiency of health care providers to address the whole patient.

“A lot of folks are just looking for any sign that this might be a safe place for them to share this information,” said Glenn.

With dedicated administrative positions and focused efforts, South Carolina health care is making strides to understand and address the experiences of the LGBTQ community.

Glenn is the first person to be in the role of director of LGBTQ+ Health Services and Enterprise Resources at the Medical University of South Carolina. He is an advocate for the LGBTQ community in patient services, in employee engagement and within the university curriculum and among students.

He noted that health professionals need to be aware of the specific challenges LGBTQ people experience to provide pertinent care.

“There’s a scarcity of competent health care providers – people who have received the education and the training to understand the unique needs and experiences of the community and provide the care that they need,” said Glenn.

This undersupply swells in rural South Carolina, where there are fewer providers.

Filling a persisting gap in care experiences, members of the LGBTQ community have resorted to circulating directories of medical and mental health care support they have identified as safe. The Alliance For Full Acceptance has created one for South Carolinians on its website at affa-sc.org.

While feeling safe to disclose sensitive information is necessary for everyone to access adequate care, the risk varies among patients.

“The LGBTQ community isn’t a monolith. Even within the community, you have all sorts of different experiences,” said Glenn. “As with any minoritized community, those living at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities, their experiences can be compounded even more as far as the discrimination they face and barriers to access and care.”

Beyond the doctor’s office, Glenn emphasized the detrimental impact on health of other forms of discrimination, such as housing and employment. These stressors can compound in minority communities and affect an individual’s health.

“The community is at risk,” said Glenn.

“Our trans community in particular is especially vulnerable: higher rates of HIV and STIs, high rates of victimization, high rates of suicidal ideation, depression and anxiety,” said Glenn, additionally noting “higher rates of breast cancer among lesbians; higher rates of alcohol, tobacco and drug use among the LGBTQ community broadly. LGBTQ youth are especially vulnerable.”

When health care cultures are not conducive to disclosing the context LGBTQ patients exist in, valuable knowledge can be lost. Many providers are not collecting sexual orientation and gender identity patient information.

“If you don’t know this basic information about patients, then you are missing a very important piece of their health profile,” said Glenn, urging those interacting with patients to have these conversations. As a transgender man at 43 years old, Glenn himself has never once been asked by a provider and has always had to volunteer the information.

It can be asked for on an intake form, but there are many ways offices can signify being a safe place, such as badges worn by staff or marketing materials and advertising of LGBTQ-specific services in the waiting room.

“Starting with what happens before physicians even open their mouths is the most important part to helping patients get that confidence,” agreed Dr. Mike Guyton, medical director of the Prisma Health Division of Adolescent Medicine, otherwise known as “Dr. Mike.” In his position, Dr. Mike conducts clinical care, educational outreach and patient and community advocacy.

He leads with nonverbal cues, having stickers of the pride, trans and straight-alliance flag on the window of the office.

“Those are a signal to those who it’s important to that this is a safe place, that this is a place where you know that as soon as you walk through the door, you are entering an open, safe, non-judgmental space,” said Dr. Mike.

At Adolescent Medicine, physicians and staff practice language with their patients that demonstrates awareness and models communication. Team members introduce themselves with their personal pronouns, giving patients an opportunity to introduce themselves that way and start the conversation of their experiences or, if they don’t know what pronouns are, creating an opportunity to teach.

Extending education to patients, practicing physicians and the community, on April 7 and 8, MUSC presented its inaugural LGBTQ+ Health Equity Summit. The two-day virtual, free-to-attend event brought thought leaders together to disseminate knowledge and increase awareness of health care and equity, covering topics such as trans mental health and how families can support their LGBT youth.

From the work of Glenn, Dr. Mike and teams allied with their mission, system-level changes and individual actions are coalescing to create safe spaces for the LGBTQ community and an improved health care system that better addresses the nuances underlying patient care needs.

By Molly Sherman