A lot of things that became essential during the heart of the COVID pandemic have gone the way of paper files and the $2 gallon of gas. Remember double masking, wearing sterile gloves to the supermarket and washing your groceries in the garage?

Telehealth, however, is not only hanging on, but its future, especially as technology expands, is looking good.

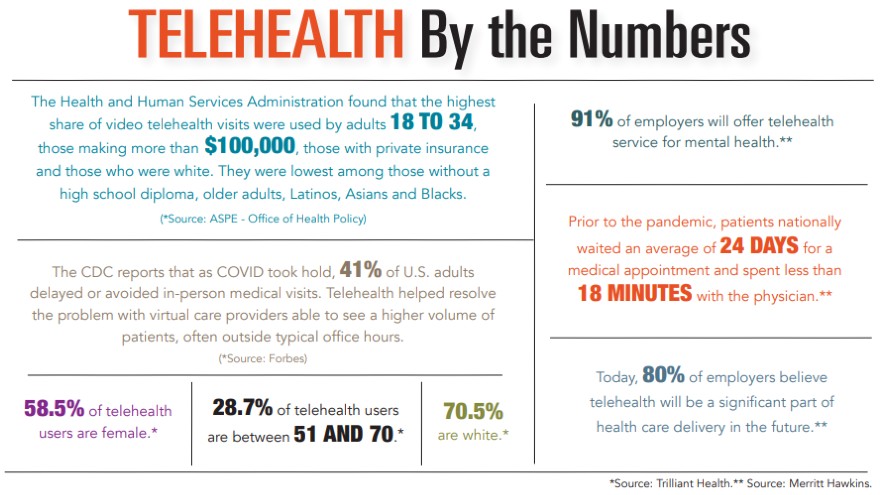

Telehealth is an umbrella term for a number of methodologies, including virtual visits that connect physician and patient through visual and audio technology, phone calls and the sharing of data from wearable or implantable devices. Prior to COVID, fewer than 1% of patient medical visits were done remotely, while at the height of the pandemic, that number rose to 45%, according to modernhealthcare.com.

Helping to drive adaptation across the board is an increasing acceptance of wearable tech and a focus on increasing development of new medical devices utilizing artificial intelligence and driven by the accessibility of 5G networks.

Technology has always been a part of Dr. Darren Sidney’s practice. Dr. Sidney is an electrophysiologist with Charleston Heart Specialists, where implantable tech – pacemakers, defibrillators and wearable heart monitors – have been around for years.

Electrophysiologists specialize in treating heart rhythm issues so their patients are used to being monitored remotely.

“All the devices we implant have remote capability,” explained Dr. Sidney. “So we can see what their heart rhythm is doing from anywhere in the world.”

New wearable devices such as KardiaMobile’s EKG, Apple Watch and Samsung Galaxy Watch 3, now approved as Class II medical devices by the Food and Drug Administration, are helping Dr. Sidney consult with patients without bringing them into the office.

“Every day, I get emails from patients sending me strips,” said Dr. Sidney, who is on staff at Trident Medical Center. “More often than not, we’re talking them off the ledge. But sometimes we do find something abnormal, and we’re able to prescribe medication, walk them through some things or triage the situation – like do they have to come into the office or go to the ER.”

For his specialty, this immediate access to information is critical. He anticipates some of the implantable tech will fall off as more and more patients become tech savvy and comfortable with wearable tech. But a big part in the equation, he believes, will be whether insurance companies develop codes to make charting and billing for telehealth visits easier and if they ever cover wearables such as FDA-approved smart watches.

“That will open the floodgates,” he said. “It will be a game changer.”

Communicating health data with your physician is one modality under the telehealth umbrella. Another is visits, which Dr. Sidney’s practice offers but does only a few each month.

“My preference for a first-time visit is in person,” he admitted, adding that “By the time they

get to me, most patients have seen a primary care doc, a cardiologist and have had some kind of imaging. A lot of times, we know what the plan for these patients is before we even meet them.”

That’s not the case for Dr. Steven Newman, a primary care physician with Poinsett Family Practice in Greenville.

When COVID hit, “we needed to convert as many patients as we could to a virtual visit,” he said.

The practice went from 2% of telehealth visits to 90% within a week. Now, as COVID wanes, Dr. Newman finds 20% of patients are making the choice to do virtual visits because they like “the platform and its convenience.”

He cautioned that there is a “fairly limited spectrum of conditions amenable to be done virtually.” In that spectrum, he includes mental health and notes that “counseling about depression, anxiety, OCD, PTSD and those types of modalities clearly don’t need a physical exam.”

Statistics that show behavioral health is a significant driver in the increase of telehealth visits. The increased accessibility at more medical practices is also helping to bring mental health services to underserved communities where no current practice exists.

Where will all this go?

Dr. Newman expects to see readily available devices in two to five years that will “measure vitals with much greater accuracy and may even be able to transmit electronically to labs.” A quick finger stick to measure cholesterol, potassium, sodium and blood sugar may all be accessible at home, he believes. But the big unanswered question is: Who’s going to pay for it?

Another big question lingers for Dr. Newman who, as a primary care physician, is on the front lines of patient diagnosis.

“We have to be very careful about not overutilizing virtual visits even though they are clearly convenient. Convenience is not always without a price. The price is you can’t develop relationships as easily with people with a Zoom meeting or a phone call. There is the element of human touch, of holding someone’s hand when they’re depressed. … You can’t do that over the phone. The patient and the physician have to understand that we cannot lose the humanity that makes the doctor-patient relationship one of the most sacred in the world.”

By Laura Haight