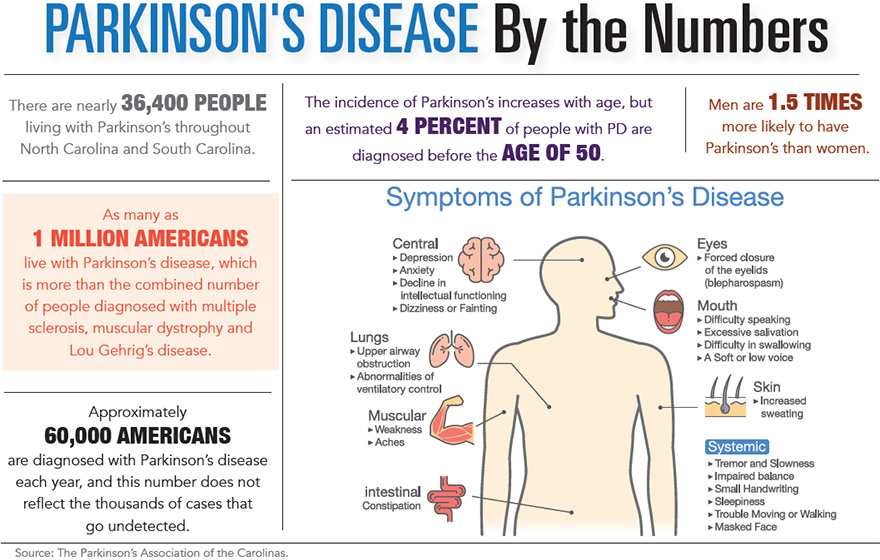

As many as 1 million Americans live with Parkinson’s disease, which is more than the combined number of people diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy and Lou Gehrig’s disease. In the Carolinas, some 34,000 people are living with the disabling disease alone.

“Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative condition after Alzheimer’s,” explained John Lehr, president and chief executive officer of the Parkinson’s Foundation. “The number of people with PD will increase substantially in the next 20 years due to the aging of the population.”

“People do not die from Parkinson’s disease; they die with it,” said Laryn Weaver,

executive director of the Greenville Area Parkinson Society, a non-medical organization. “The symptoms may cause other health issues which often contribute to the patient’s decline.”

According to the Greenville Area Parkinson Society, symptoms are tremors; rigidity; balance issues; slowed speech; a decrease in volume when speaking; loss of sense of smell; a decrease in fine motor skills such as writing; constipation; body aches; depression; difficulty swallowing; restricted facial expressions; dementia; and hallucinations. Some patients experience all these symptoms and others just a few, and some patients exhibit the physical effects but not the mental deterioration. There are cases where patients lived 20 to 30 years after being diagnosed and others who declined rapidly and passed away within a few years. The latter most likely had a different version of atypical Parkinsonism such as lewy body dementia, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal syndrome.

Lehr said most people with PD are diagnosed in their 60s.

“In rare cases, some people will develop PD before age 50, known as young-onset PD. Men are 1.5 times more likely to have PD than women. Directly inheriting the disease is quite rare. Only about 10 to 15 percent of all cases of Parkinson’s are thought to be genetic forms of the disease. In the other 85 to 90 percent of cases, the cause is unknown.”

According to Dr. Vanessa Hinson, professor of neurology and director of the MUSC Parkinson Foundation Center of Excellence, the most important recommendation for managing Parkinson’s disease is to see a movement disorders neurologist.

“This type of doctor specializes in Parkinson’s disease and will be most sensitive and knowledgeable about the patient’s issues,” she said.

At the Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence at MUSC, a group of seven movement disorders specialists, nurse practitioners, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists and rehabilitation specialists work as a team to offer each patient a comprehensive approach to Parkinson’s care. This includes up-to-date medication management, consideration of surgical options, Parkinson’s-specific rehab and access to Parkinson’s disease research studies.

Although there is no known prevention, there is now understanding about which protein is responsible for damaging brain cells in people with Parkinson’s, and there are new approaches on how to combat this process.

Weaver said, “There is still no cure, but exercise can significantly improve the quality of life.”

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery was first approved in 1997 to treat Parkinson’s disease tremor, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation, then, in 2002, for the treatment of advanced Parkinson’s symptoms. More recently, in 2016, DBS surgery was approved for the earlier stages of PD – for people who have had PD for at least four years and have motor symptoms not adequately controlled with medication.

“DBS is certainly the most important therapeutic advancement since the development of Levodopa. It is most effective for people who experience disabling tremors, wearing-off spells and medication-induced dyskinesias, with studies showing benefits lasting at least five years. That said, it is not a cure, and it does not slow PD progression. It is also not right for every person with PD. It is not thought to improve speech or swallow issues, thinking problems or gait freezing,” he said.

Dr. Hinson said exercise can keep Parkinson’s symptoms mild and slow down the progression of the disease.

“People with Parkinson’s who exercise a minimum of 30 minutes three days a week seem to progress slower than those with a more sedentary lifestyle. It is clear that high intensity workouts, where you break a sweat, have more of an impact than a stroll around the block. Most important is the frequency and intensity of the workout,” Hinson pointed out.

A Parkinson’s-specific exercise class that has shown great effects is Rock Steady Boxing at MUSC. Certified instructors work with a group of Parkinson’s patients in a high-powered, non-contact boxing class that provides an immensely motivating and powerful environment for patients.

Dr. Hinson said, “The benefits of exercise are not just limited to moving better. Research has also shown that exercise halts the onset of cognitive decline and improves mood.”

Dr. Hinson mentioned that families of patients can help them manage Parkinson’s disease.

“If care partners attend medical appointments with the patient, they can learn more about Parkinson’s, its effects on the patient and ways they can help. Understanding why the patient cannot do certain things is important and will foster patience, but, on the other hand, learning about what they can and should be empowered to do is equally essential. It is important for the caregiver to remain supportive and keep encouraging the patient even on days when things are not going well,” Dr. Hinson said.

By John Torsiello